|

Introduction

Lissa Tyler Renaud

Editor, "Kandinsky Anew" series

When the topic of discussion is Kandinsky, it is usually the art

historian's voice we hear, or the more or less informed enthusiast.

But we don't usually hear Kandinsky's poetry discussed by poets,

or his plays discussed by playwrights. By the same token, we rarely

hear Kandinsky's paintings talked about by a painter—and a

painter who can write—and that is what we have here with painter

-poet David Wiley.

Wiley's path to understanding a painting is informed by deep

knowledge of art theory and art history. And yet, he writes here

about looking at Kandinsky's works: "It didn't help to stare at the

paintings and try to analyze them. What they were telling me had

little to do with analysis." What a pleasure it is, then, to listen in on

a painter's inquiry and insights into the circle in Kandinsky's

paintings, and to follow along with his delightful, intuitive thought

process.

It certainly takes a deeply intuitive person to connect Kandinsky,

circles, and—well, I will not give away the punchline to Wiley's

story. But in the spirit of his own associative process, his story

suggests to me a story that was hidden until not that long ago: In

1914, when WWI began, Kandinsky was ejected from Germany as

an enemy alien after a longtime residency there. He returned to

Russia. In 1917, the 50-year-old Kandinsky married the 17-year

-old Nina Andreyevskaya, and they had a son later that

year—Vsevolod, or "Lodya." But like countless children during the

Civil War in Russia, their child did not survive the

malnourishment and diseases that were rampant; he died in 1920,

just shy of three years old.

The Kandinskys, themselves enduring enormous privations,

buried the child there in Moscow. They left for Berlin not long

after, with an agreement never to mention their child abroad.

Their colleagues in Germany never knew that the Kandinskys'

disappearances were for trips to visit their child's grave. Indeed,

scholars also never knew of, or never mentioned, the child. As a

result, when I began formally to study Kandinsky in the early

1980s, this important part of Kandinsky's life in wartime Russia

was invisible, and could not offer the poignant, personal context

for his artworks after 1920.

Even with the information available now—with the Iron Curtain

open, and Nina gone—the death of Kandinsky's son doesn't seem

to figure in discussion of his paintings. I wonder if the death of

that child plays a role, in a mysterious way, in David Wiley's

intuitions.

Considering Kandinsky's Circles:

A Painter's Adventure of the Mind

by David Wiley

There is often a good deal of serendipity involved in adventures of

the mind. When a series of mental events leading to a possibly

meaningful conclusion occurs, it is not unusual for this conclusion

to be dependent upon something unintended and unforeseen, just

as the "accident" that happens in a painting may point the artist in

a new and more fruitful direction. It was Aristotle's notion that

genius is the rapid perception of the relationships between things.

Although it seems incomplete, I have always liked this definition

of genius. The practice of art is certainly a process of finding the

relationships between things, physical and abstract, and using

these relationships in a significant and moving way. The challenge

for the artist is to harmonize and compose the parts.

During a trip to New York City, I spent a few hours in the

Guggenheim, mostly looking at the exhibition of Kandinsky

paintings from his Paris period. As I gazed rapturously at these

paintings, some of which I had never seen, my thoughts turned to

earlier Kandinsky paintings. As I looked at the paintings, trying to

regard them without prejudgment of any kind, they began to

speak to me, they began trying to tell me something that I didn't

understand and needed to understand. It was a fairly urgent

message, it seemed to me, but one I simply could not decipher.

Plato's saying that all knowledge is but remembrance came to

mind. It was something I knew somewhere in my being, and I was

trying to drag it up through the smoke and mirrors and chaos of

the subconscious. It didn't help to stare at the paintings and try to

analyze them. What they were telling me had little to do with

analysis. The more I tried to figure out what the voice was saying,

the fainter it became.

|

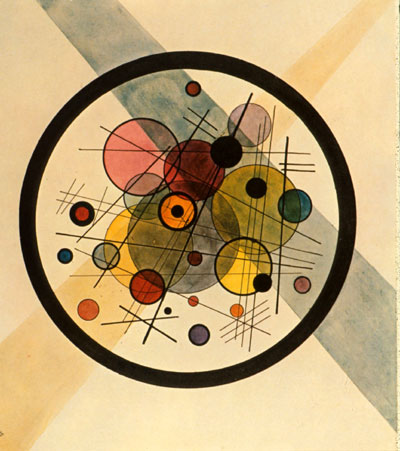

Kandinsky, "Circles Within a Circle," 1923

Kandinsky, "Accent on Rose," 1926

As we left New York the next day, I was still scouring my mind for

an answer. It was annoying, like forgetting a familiar word or

name. Shortly after we arrived in California I met up with my

niece Gabey, who was nine months pregnant, and I remarked to

her that she reminded me a little of Kandinsky, with her

semispherical belly. This observation did not produce an answer

to the question that had been nagging me persistently, but, as it

turned out, the sight of Gabey's belly was a stepping stone, a

station along the way in my mental treasure hunt.

Two days later, as I was sitting in my studio thinking about

Kandinsky again and trying in some way to resolve the matter that

had been tormenting me for four days, my thoughts turned to

another one of my favorite painters, Alexei Jawlensky, who, along

with Kandinsky, Klee, and Feininger, was one of "The Blue Four."

Then my thoughts went back eight years to my miraculous

discovery of a large exhibition of Jawlensky paintings in a small

museum at the edge of a little medieval town on the Danube,

about eighty miles from Vienna. My companion and I had taken a

river excursion boat from a place called Krebs to the town at the

end of the line. Here my memory failed me, not in the Platonic

view, but in the normal, human sense. Determined to get the

answer to this question, at least, I found my Vienna guidebook and

turned to the page where there was a graphic of that stretch of the

Danube we had covered. I scanned the irregular line of the river,

stopping at some of the historic sites along its banks, the castle

where Richard Lion Heart had been imprisoned, and so on. Just

before coming to Melk, the town where we had serendipitously

found the Jawlensky exhibit, the town whose name I had forgotten

, my eye stopped at another ancient place along the river, the

village of Willendorf, just above Melk. Here a wealth of Neolithic

artifacts has been uncovered, including the famous Venus of

Willendorf, a 24,000 year old limestone sculpture of a rotund,

pregnant woman. I reflected that the Neolithic artists painted and

sculpted according to what they understood was important. And

one of the things that was very important to them was fertility. In

the guide book there was a tiny drawing of the Venus, and as soon

as I focused on it the proverbial light above my head turned on. All

the pieces of the puzzle fell into place, as they say. What

Kandinsky's paintings had been trying to tell me was that they

were about fertility. Cosmic fertility no less.

|

"Venus of Willendorf"

It wasn't just the circles, which of course may represent many

things, nor was it that the sphere is the most potent and

fundamental of all symbols; it was the way Kandinsky's circles and

triangles and swirls and trapezoids and trapeziums all intermingle

in a three dimensional way, creating an impression of cosmic

intercourse. Geometric or not, Kandinsky's highly symphonic

compositions are bursting with energy and life.

Kandinsky, "Around the Circle," 1940

The urgency of the message, I believe, had to do with the fact that

I am a painter, and of late my work has been going in a

Kandinskyish direction, for reasons unknown. This little

adventure of the mind, resulting in the eventual apprehension of

"cosmic fertility," has given me a welcome concept to work with,

the kind of concept that involves the simple, the obvious, the

mysterious, and the complex.

As a coda to this business, perhaps a theatrical production could

be created based on the story. It could have Neolithic people

making art and other things, cosmic scenes and events, triangles of

every possible kind, and all known shades of color, each one

making a sound of its own and emitting a fragrance different from

all others.

Kandinsky, stage set for "The Gnomes,"

Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, 1928

|