|

I recently

had surgery to remove a

cataract from my right

eye. Over the previous

year, that eye had

grown increasingly

blurry until using it

was like looking

through a lens coated

with Vaseline. My left

eye was still close to

100% functional, which

was fortunate, but also

made it difficult to

read, especially at

night, as the two were

no longer working

together. Therefore,

despite some

nervousness—the

thought of someone

plying a scalpel on my

eye was daunting to say

the least—I

scheduled the operation.

The surgery in fact

went quite well. It was

painless and quick,

about 30 minutes, and

the only difficult part

was going without food

or coffee all day.

During the first

post-op hour or so, I

didn't see much

improvement as the eye

was still recovering,

but on the way home, I

noticed that things

seemed clearer and

brighter, though since

it was dusk, the change

wasn't dramatic.

It wasn't until I

arrived home that I

first experienced the

impact of how much

improvement had been

made. Upon walking into

the lobby of my

apartment building, I

felt as if I had walked

on stage. The room was

filled with a

brightness I hadn't

perceived in many

years, and the hallway

leading to my unit was

dazzling. By the

following morning, this

new clarity was fully

realized: For the next

several days, I was

amazed over and over by

how bright the world

was, how blue the sky

and how white the

clouds. It was

literally like being

given new eyes.

Several days later, I

was meeting my writing

coach with whom I am

working to expand some

of my non-fiction into

a book. I described the

surgery and its

aftermath. Knowing of

my passion for art and

familiar with some of

my writing about it,

she suggested I visit a

museum and write about

what it was like to

view familiar works

with my improved

vision. I thought this

an excellent idea, so I

went to the Phillips

Collection in D.C. and

revisited their current

exhibition, "Breaking

It Down: Conversations

From the Vault." This

show comprises entirely

works from the

collection displayed in

such a way as to spark

conversations between

and among them. In some

ways, it was a

mini-retrospective of

the museum as I had

first encountered it

when I was newly

arrived in Washington

and it consisted of the

original Phillips house

and a slight extension.

Artworks that showed

affinities with each

other or which arose

from the same movements

were grouped together

in a manner that was

quite revelatory and

provoked much thought

about origins and

historical import. For

example, as soon as one

entered, one faced a

staircase, around which

were grouped three

paintings, a Matisse, a

Dufy, and a Diebenkorn.

The Matisse and

Diebenkorn in

particular spoke to and

illuminated each other.

I wasn't too familiar

with Richard Diebenkorn

at the time and seeing

his picture alongside

Matisse's was a

revelation and the

beginning of a strong

life-long admiration

for his work.

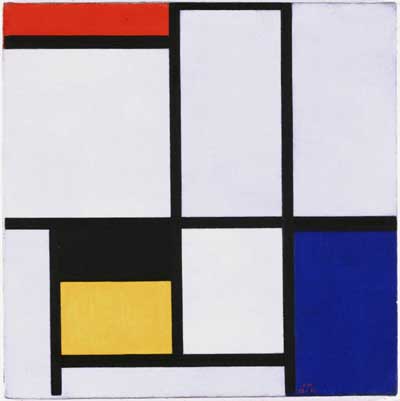

One of the first works I encountered was this classic Mondrian.

Piet Mondrian, Composition No. 3

I like Mondrian's work, but it's mostly an intellectual pleasure,

devoid of the emotional impact that my very favorite artists

deliver. Nevertheless, with my freshened vision, these simple

primary colors appeared rich and the sharpness of the contrast

between the colors and the white background was striking.

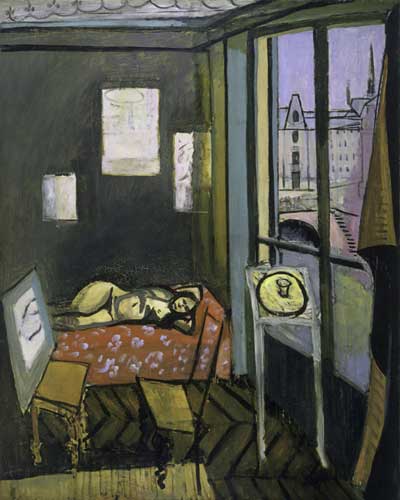

In the same room as the Mondrian, I found two of the three

paintings that I had stood in awe of those many years before in

the stairway.

Henri Matisse, Studio, Quai St-Michel

Richard Diebenkorn, Interior with View of the Ocean

Though the Matisse displays no especially bright colors, its dark

richness became apparent, especially in the brightly lit gallery,

while the Diebenkorn—showing the clear influence of

Matisse—dazzled with its bright airiness. It shone out much

brighter than in the dim stairway where it resided in my early

days of visiting, something that would have been noticeable even

before my surgery.

Richard Diebenkorn, Ocean Park No. 38

This nearby work, from the acclaimed Ocean Park series that

depicts sunny California landscapes abstracted to color and line,

rocked me back on my heels with its brilliant colors—one could

almost feel the warmth of the sun.

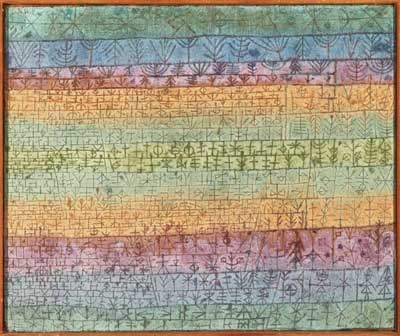

I moved to an adjacent gallery and found myself confronting an

array of works by Paul Klee, an artist I love greatly, in both an

emotional and aesthetic sense. Back in the 80s when I lived in the

Mount Pleasant neighborhood of D.C. and worked nights, I would

often leave for work a couple of hours early and stop into the

Phillips just to visit one or two galleries that contained favorite

paintings. (The museum offered free admission back then.) My

most favorite was a couple of rooms that held Klee and his

contemporary, Wassily Kandinsky. So I was thrilled to pass along

in front of almost every piece in the Collection's Klee unit. It goes

without saying that once again, these works had the effect of

appearing to me in the fullness of their color and images as if for

the first time. One in particular, though, really hit different.

Paul Klee, Tree Nursery

In addition to lovely layers of color, the incisions representing

trees stood sharp and clear. Klee incised all of them into the

surface before adding color and I was stunned by the delicacy and

precision of each tiny tree.

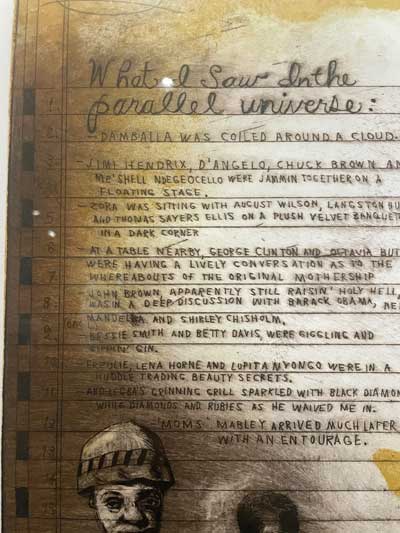

Renée Stout, What I saw in the parallel universe (photo by the author)

Renée Stout was a new discovery for me, the latest of many I've

made over the years at the Phillips. In the case of this image, it

wasn't so much the color or imagery, but the clarity of the letters

making up the text overlaying the images that really stood out on

this repeat viewing. I have always been fascinated by art that

mixes images and text and Stout has created a masterwork of the

genre.

Stout's painting has been juxtaposed to a fine Sean Scully

(another remarkable artist I first encountered at the museum).

Sean Scully, Day

Scully's abstract works display an affinity with such modernists as

Mondrian and Mark Rothko, but the earthy tones—richer and

more vibrant to my newly clear eyes—reflect his travels in Mexico.

I was wowed the first time I saw Scully's work and even more so

on this encounter.

This exhibition contains a plethora of amazing artworks from the

permanent collection, many not seen in years, including pieces by

Sam Gilliam ( a D.C. native and local hero). Georges Braque,

Arthur Dove, Georgia O'Keefe, Joel Meyerowitz, and numerous

others. It runs through January 19, 2025, and I strongly

recommend that if you are in or near the D.C. area you go see it at

least once.

It wasn't only works in the show, however, that I saw through new

eyes. Long-time loves also shone out freshly and powerfully. For

example, Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell, August, Rue Daguerre

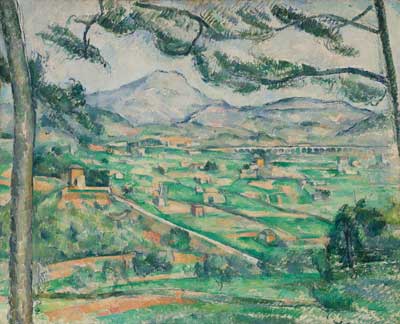

Or Paul Cézanne.

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire

And Bonnard.

Pierre Bonnard, The Terrace

Even that old war horse Renoir's Luncheon of the Boating Party looked fresh and sparkling.

Of course, I cannot visit the Phillips without entering the Rothko

Room, usually my final stop before refreshing myself in the café.

https://www.phillipscollection.org/curation/rothko-room

I must confess that I approached it this time with some

trepidation. The emotional, even spiritual power of these works is

the most intense experience of art that I know. I feared being

overwhelmed. I entered slowly, then stopped, almost gasping. The

paintings virtually glowed, shimmering, giving off auras of

indescribable radiance. Transcendent is a most overused word

these days, but it's the only one I can think of to describe the

impact of these four remarkable paintings. I drank and breathed

them in, individually and as a whole.

I walked out of the museum in an emotional state I have no words

for. Even the sunlight of the day seemed a little duller after the

visual feast I had just consumed. I made my way to a nearby

coffeeshop (the Phillips' being too crowded) and made some

notes and thought deeply for a long time about what I had

experienced.

I must thank Dr. Gregory Gertner, my eye surgeon, for his skill in

giving me restored vision in my right eye. Also, much gratitude

to my amazing writing coach Randon Billings Noble for

encouraging me to write this essay.

|