|

In general, people who

know of Wassily

Kandinsky (1866 –

1944) know him from the

perspective of his

painting life, and many

also recognize him as

the instigator of

abstraction in

painting. In fact, he

also had a theatre

life, and is still

today among the most

daring of those who

have created abstract

works for the stage.

In his day, Kandinsky's

plays and his thinking

about the theatre were

hailed by innovators as

theatre-altering as

Hugo Ball, founder of

Dada, and Oskar

Schlemmer, founder of

the Bauhaus Theatre.

Kandinsky's "stage

compositions" also

brought him into

contact with other

seminal theatrical

figures such as

Diaghilev, Massine,

Stanislavsky, Breton,

and many more.

It is exciting to bring

"into the fold"

Kandinsky's work and

influence beyond

painting, and even

beyond his

commodification by the

art world.

What follows is meant

to give readers a kind

of reference guide, a

chronological

scaffolding for

understanding the

mostly extra-painting

articles to come in

this series: where he

was, what he did, who

he knew—that kind

of thing.

Hoping it contains

interesting surprises

for those just coming

to Kandinsky, as well

as for the expert and

the devotee.

*

Kandinsky's life, like

his thinking about art,

was a process of

unifying or merging a

range of sprawling,

complex elements. He

was a Russian who lived

primarily in Germany,

then spent the last

years of his life in

Paris. At the opening

of his career in

Germany and at the

close of it in France

he was considered a

Russian artist, but his

Russian compatriots

associated him with the

romanticism and

subjectivity of the

German art scene. He

held citizenship papers

in each of these

countries at different

times, speaking each of

their languages. He

traveled in many more

countries than he lived

in, and studied still

more. Ultimately, even

when he had a choice,

both as an artist and a

person he claimed the

right to be a true

"world

citizen."

Along with the

sensibilities that he

culled from around the

world, Kandinsky's

work life unified his

various areas of

training and interest.

He was armored as a

critic and organizer by

professional training

in law and economics.

He was supported as a

teacher of "the

science of art" by

the methods of

systematic inquiry he

used doing ethnographic

research as a

university student. As

a painter, he learned

anatomical drawing and

color theory from one

teacher, Anton AŇĺb√®,

and the flow of forms

from another, Franz

[von] Stuck, blending

these two influences

into an art that

extended beyond the

realms of both.

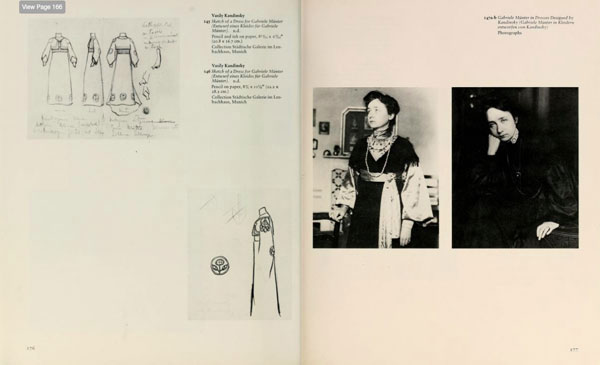

At left: Sketches for dresses for the painter Gabriele M√ľnter, early 1900s. At

right: Gabriele M√ľnter in dresses designed by Kandinsky. In the Kandinsky in

Munich catalogue, 1982, from the Collection Städtische Galerie im

Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Kandinsky also looked for ways to unify—to "synthesize"—his

other interests. He was an accomplished amateur on the piano

and the cello. He wrote poetry. At the turn of the century he

sketched period peasant costumes, and designed dresses,

embroidered purses and hangings, and jewelry. At various times

during his life he also designed wall murals, furniture, vases, and

dishes. These interests in the sets, costumes and props of

everyday life, as well as in music, poetry and the dramatic impact

of a visual image, reveal a temperament that we can see might

find satisfaction in the theatre.

In fact, it was to the theatre that Kandinsky turned for a place to

synthesize his experiences and abilities. Over a period of 35 years,

in Germany, Russia and France, as dramaturg, dramatist and self

-appointed demiurge of the art world, Kandinsky pursued his

elusive, monumental vision—what he called the Synthesizing, or

Unified, Art of the Stage.

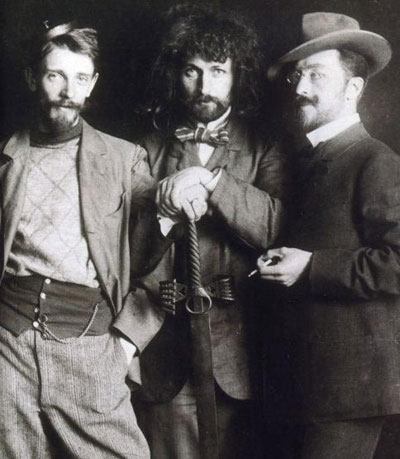

Painting students at Anton AŇĺb√®'s school, Munich, 1897.

(L to R) A. Seddeler, Dmitry Kardovsky, Wassily Kandinsky.

When Kandinsky came to Munich from Moscow to study painting

in 1896 at the age of 30, he had already been struck by the power

of the theatre, by a production he had seen of Wagner's

Lohengrin. Maybe it was because of this that his activities in

Munich brought him into contact with many people who were

involved in performance. In 1900, he co-founded Phalanx, an

association of young artists who exhibited their works together.

One member of this group was Alexander von Salzmann, who

later engineered the revolutionary lighting designed by Adolphe

Appia for Jacques-Dalcroze's School at Hellerau. Peter Behrens

both exhibited with Phalanx and played an influential role in

Munich's experimental theatre circles. Behrens worked closely

with Georg Fuchs, the great theatre reformer, who was also to

become more than tangentially associated with Kandinsky a few

years later.

Other members of Kandinsky's society were concurrently

involved with a group of avant-garde cabaret performers called

Eleven Executioners (Elf Scharfrichter). One was a sculptor

named Husgen, who designed masks. Another was Ernst Stern,

who designed the group's sets and posters, and who eventually

designed for Max Reinhardt's theatre in Berlin. It is interesting to

note that two other members of the cabaret group were the

playwright Frank Wedekind, who sang, and Reinhard Piper, who

was to become Kandinsky's publisher. The Phalanx association

continued through 1904.

In 1902, Kandinsky wrote some art correspondence for a journal

that was edited by Diaghilev, called The World of Art. In this

context, Kandinsky came close to knowing more of Anton

Chekhov than just his plays; Chekhov's letters include one to

Diaghilev in 1903, in which he refused Diaghilev's invitation to

become editor of the journal. Although the art correspondence

was his only writing for Diaghilev, Kandinsky followed the

publication closely, and surely knew Diaghilev's work in the

theatre. Aside from the fact of Diaghilev's prominence in the

Russian avant-garde, Kandinsky took an interest in the work of

Leon Bakst, who was a painter and also a set and costume

designer for Diaghilev. Later events also involved Kandinsky

directly with Fokine, Diaghilev's great choreographer.

In 1908, Kandinsky was already thinking about writing for the

stage. In 1909 he met Thomas von Hartmann, a young Russian

composer who was studying in Munich. Hartmann wrote later

that Kandinsky was dissatisfied with the theatre in general, and

the opera in particular, from 1909; in any case, they began to

experiment together.

Their first idea was to stage one of Andersen's fairy tales. The two

of them often developed their ideas with Hartmann improvising

at the piano while Kandinsky described what was happening on

the stage. Kandinsky sketched a medieval set for the fairy tale,

and they created a play text that seems to be the same manuscript

called Paradise Garden, which was found in his papers. But that

same year, Diaghilev's Ballets Russes created a sensation in Paris,

featuring exotic designs by Bakst. After experimenting with

translating their fairy tale into a ballet, Kandinsky and Hartmann

discarded their idea and started again.

At this time, a Russian dancer named Alexander Sakharoff joined

the collaboration. The three of them made it a priority to know

something of one another's creative disciplines, and already

having some understanding of music in common, Hartmann and

Kandinsky set out to learn about dance, starting with ancient

Greek dance, while Sakharoff studied the paintings in the

museums. In this way, the next project they approached was a

staging of Daphnis and Chloe, for which Kandinsky again

sketched a set for the opening scene, "a marvelous trireme with

warriors, by no means a realistic picture, but it conveyed an

astoundingly strong impression of Daphnis' terror."

We hardly ever hear about the association of Kandinsky,

Hartmann and Sakharoff without a quotation from Kandinsky's

own description of how they experimented, trying to find the

currents that connected their respective arts:

From among several of my watercolors the musician would

choose one that appeared to him to have the clearest musical

form. In the absence of the dancer, he would play this

watercolor. Then the dancer would appear, and having been

played this musical composition, he would dance it and then

find the watercolor he had danced.

Kandinsky thought that whatever the three of them found by

studying together would not only prove the inter-relatedness of

their arts, but would also teach him something about painting.

Twenty years later he wrote: "It is more profitable for an artist to

acquire specialist knowledge of some unfamiliar subject, provided

he is able to develop the... capacity for analytical-synthetic

thought, than to be narrowly 'educated' in his own subject."

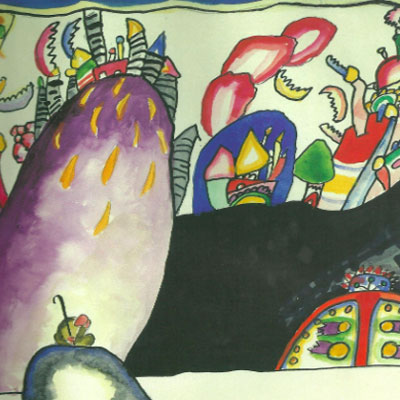

Kandinsky wrote four plays in the years 1908-9. These were Stage

Composition I, Voices, which came to be retitled Green Sound; Giants, which was revised and retitled Yellow Sound in March of

1909; Stage Composition III, Black and White; and Stage

Composition IV, Black Figure.

Georg Fuchs opened the Munich Artists' Theater in early 1908,

and that might have given some impetus to Kandinsky's stage

projects. There is no doubt that Kandinsky knew Fuchs' writings

on innovative theatre, which were related to the groundbreaking

ideas of Adolphe Appia (Swiss) and Edward Gordon Craig

(English). Fuchs' work was the talk of Munich art circles, and two

of Fuchs' articles even appeared in the same journal, Apollon, that

Kandinsky contributed art reviews to in 1909-10. Kandinsky's

own writings on the theatre resemble some of Fuchs', but we will

never know whether Fuchs actually influenced Kandinsky, or just

corroborated what he already felt to be true. Having collected his

own ideas for as many as twelve years, Kandinsky finished writing

his first book, On the Spiritual in Art in 1910. It was published the

following year. This early book already contained a discussion of

"new dance," with reference to Isadora Duncan; it also introduced

the principles of "the theater of the future" that Kandinsky would

invoke for the rest of his life.

Friends of The Blue Rider on the balcony of M√ľnter and Kandinsky's

apartment at Ainmillerstrasse, 36, Munich, 1911. L to R: Maria and

Franz Marc, Bernhard Koehler, Wassily Kandinsky (seated), Heinrich

Campendonk and Thomas Hartmann.

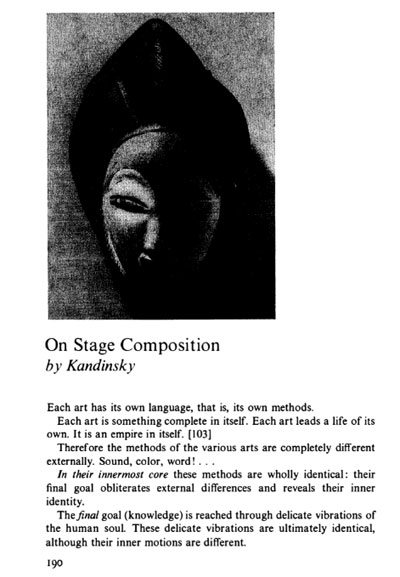

Of all of the plays Kandinsky had written, he singled out Yellow

Sound to work on over the longest period of time. He finished it

in 1912, and published it the same year in the Blue Rider Almanac, an inter-disciplinary collection of pieces he edited with his great

friend, the painter Franz Marc. Before the text of Yellow Sound,

Kandinsky included a full essay, "On Stage Composition." In it,

Kandinsky talks about his theories of dramatic art at some length,

particularly making clear the distance between his own

conception of the "synthesizing" stage art and Wagner's

gesamtkunstwerk, or "total" work of art—a difference that

remained key to Kandinsky's theatrical ideas.

In 1913 Kandinsky planned to illustrate the Bible with, among

others, Franz Marc, Paul Klee and the Expressionist painter and

playwright, Oskar Kokoschka. In the first year of his

correspondence with Schoenberg (1911), Kandinsky had already

asked for news of Kokoschka several times, and had mentioned

seeing his paintings three years earlier, that is, when Kokoschka

first began to exhibit. 1913 was also the year that Kandinsky's

autobiographical Reminiscences appeared; it included a

description of his pivotal encounter with Wagnerian theatre. Sounds, an awe-inspiring volume of thirty-eight prose poems was

also published, and remains to this day an incomprehensibly

hidden treasure of modern literature.

The famed Dadaist Hugo Ball and Kandinsky had met in 1912

when Ball came to the Munich Artists' Theater as dramaturg after

studying and teaching in Max Reinhardt's drama school. In early

1914, Kandinsky introduced Ball to Hartmann, who had just taken

Kandinsky's script and set designs for Yellow Sound, along with

his own music, to Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theatre in

Moscow. Stanislavsky—whose tastes in theatre experimentation

ran in a different vein, and whose theatre had just been producing

Turgenev, Moli√®re, and Goldoni—had not shown any interest in

it.. Ball proposed Kandinsky's Yellow Sound for production at the

Munich Artists' Theater. It was planned to be performed with

Hartmann's music and Alexander Sakharoff dancing the leading

role. During this year, Kandinsky wrote his next known stage

composition, Violet Curtain, generally known as Violet. Perhaps

the energy for this new play came from his peers' recent

encouragement for Yellow Sound.

Wassily Kandinsky for his stage composition Violet, Picture 2, 1914. Pencil,

watercolor, ink on paper. Detail. Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

Also in 1914, Ball made plans with Kandinsky, Marc, Hartmann

and Fokine for a book to be titled The New Theater. This was to

be a sort of Blue Rider Almanac of experimental theatre.

Kandinsky was to write an article on his version of the "total work

of art," to be included with articles and stage designs by the

others. Klee and Kokoschka were to contribute designs and plays

respectively. They hoped for this association of artists to expand

into an International Society for Art, a society for modern artists

of the theatre, painting, music and dance. In a letter to

Schoenberg at this time, in anticipation of a visit from him,

Kandinsky wrote: "Here there are all sorts of theater plans, which

you have already heard about from Marc. You are therefore

awaited with particular eagerness."The "eagerness" of this letter

makes it all the more heartbreaking that every one of these plans

for play production, book, international society—and even

Schoenberg's visit—were aborted by the sudden outbreak of

World War I.

In an odd twist of fate, the resident Kandinsky and the touring

Stanislavsky, both in Germany when war was declared and, as

Russians, both suddenly now enemy aliens, found themselves

being deported together. Stanislavsky and his entire theatre

company had been held at gunpoint, and Kandinsky given 48

hours to leave. Care of a clever ruse devised by a Russian

Orthodox priest Kandinsky knew, Kandinsky and Stanislavsky

were able to escape being put on a German boat, which could

have been dangerous, and instead left for Switzerland together on

the same neutral Swiss boat!

*

Part 2 to follow:

Kandinsky's Theatre Life, 1914 to his death in 1944, and beyond…

Cover Image behind type:

"A Fluttering Figure" 1942, oil on wood

26 X 20 cm. PompidouCenter

Note: An earlier, different version of this article was developed for Dramaturgias journal, Brazil.

|

|